When Knocking Did Not Get the Door Open, Monkey Punched a Hole in It

On wuxia cinema, Conan the Barbarian, and spiritual transcendence

The Tang Dynasty, the setting of the Monkey King’s story, was the poetic golden age of Li Bai and Du Fu. This period between the seventh and tenth centuries also saw the rise of Chan Buddhism, the tradition behind Zen Buddhism that incorporates concepts and meditative practices related to Taoism. The Monkey King bounces around in that overbrimming historical moment, which continues to sustain mind-adventures.

Kaiser Kuo, who cofounded the heavy metal band Tang Dynasty in the 1980s, says on this week’s Cosmic Library, about the historical mood behind the band’s name:

Tang Dynasty was also this period of both literary and martial glory, and there had to be this connection. I thought: we’re a metal band, right? You look at metal bands in the UK or in the States and often the touchstone with them, the cultural touchstone is: Tolkien, or medievalism, or fantasy–Conan the Barbarian. It’s that kind of thing, right?

I thought there’s an analogy to that. The same kind of pimply adolescents who listened to metal in the States, like I did growing up—you know: “the hammer of the gods will drive our ships to new lands”—and all that stuff—I just thought there’s an analogy in China, which is: we all grew up reading Sanguo Yanyi (The Romance of the Three Kingdoms). And we all were into the Jin Yong martial arts epics. We all loved that stuff.

The Monkey King and Wuxia: Not the Same, Not Too Different

In this week’s Cosmic Library episode, I talk with the scholar Karen Fang about wuxia, the genre of martial arts epics that Jin Yong’s books exemplify. It’s a genre that looks to history, and it’s full of fantastical fight scenes—like Journey to the West, in a way. Karen Fang says:

The underlying idea in wuxia is this idea that somebody can reach a level of human transcendency—a transcendent power, a transcendent skill—through years of training and dedication, both to physical training, but also spiritual dedication.

The Monkey King does cultivate transcendent skills within similar spiritual traditions. But he’s not human, and there’s plenty of satirical mischief along with superhero antics in his case. Here’s a scene from the Monkey King’s fight with the demonic Red Boy, in which Monkey turns to the divine help of the bodhisattva Guanyin—it’s a scene of fighting and of spiritual engagement, in a comic mood:

Monkey somersaulted to the entrance of the cave. When knocking did not get the door open, Monkey punched a hole in it with his staff. Red Boy immediately charged into the fray, but after a few minutes Monkey fled back to Guanyin and hid in her divine aura.

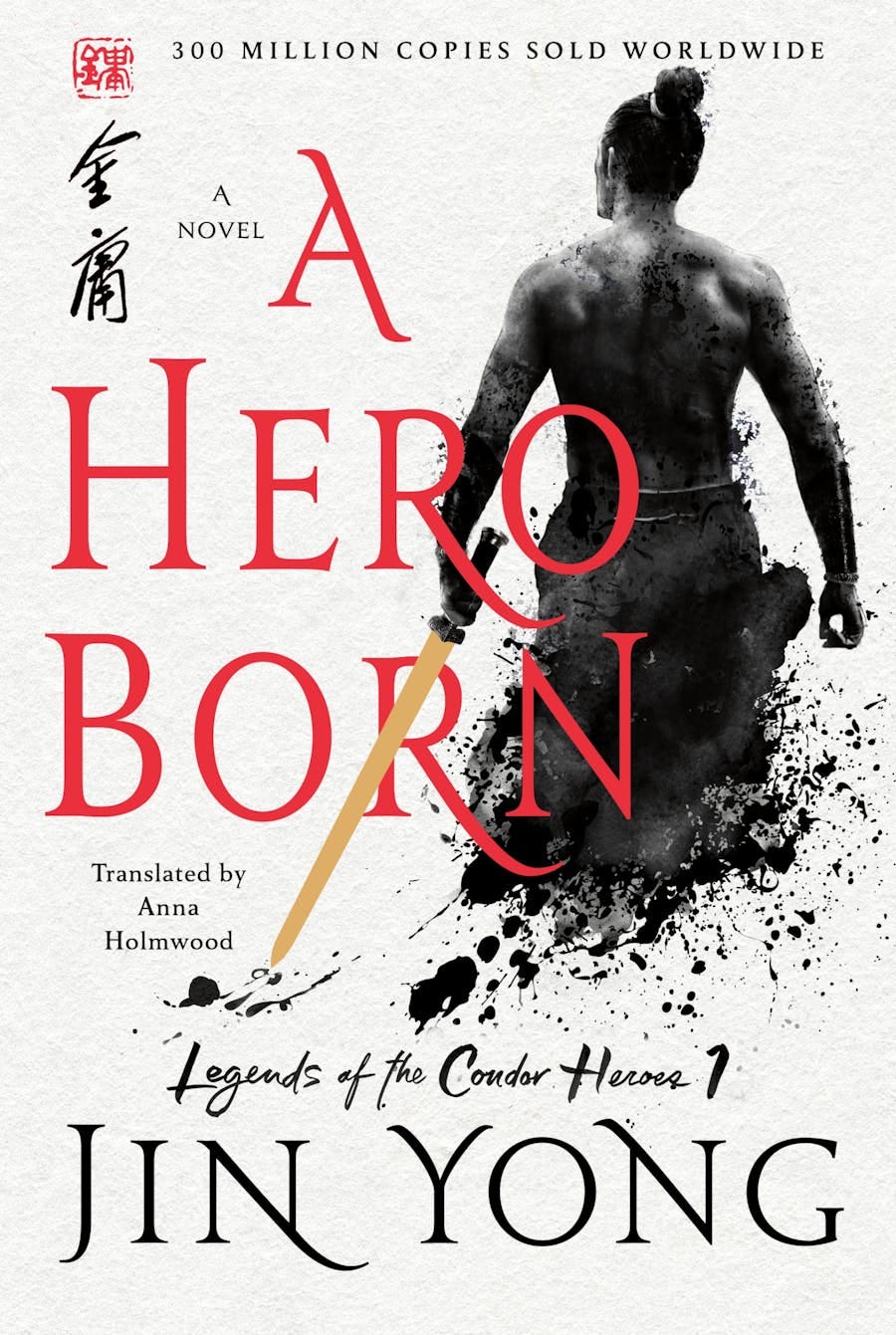

Now here’s a passage from the realm of wuxia—from Jin Yong’s Legends of the Condor Heroes series, the first volume, translated into English as A Hero Born (translator: Anna Holmwood):

Hurricane Chen had orientated himself in that moment of clarity. He gathered his qi to his left shoulder, strode straight at Ke’s staff and grasped hold of it, scratching at Ke with his other hand. Flying Bat Ke released his weapon and leaped backward. Copper Corpse clenched his fist, reached and punched Ke’s chest with the force of all his internal energy. Ke Zhen’e was blasted backward and Chen threw the staff like a spear, roaring with pride.

Physical and spiritual engagement characterize both fight scenes, with fantastical qualities. Whether the Monkey King’s comic tones undermine this whole matrix or add a new level to it—that’s one possibly irresolvable question at the heart of Journey to the West.

Next week: The Hall of the Monkey King concludes! Tell your friends! Watch wuxia films! Thank you one and all!

-Adam