In this week’s Cosmic Library, we welcome a new guest: Kaiser Kuo, who hosts the Sinica Podcast (he was also a founding member of the Chinese heavy metal band Tang Dynasty). You’ll hear him critique Journey to the West’s endless recurrence in pop culture outside of China. When I asked what he’d like to see more of instead, his answer was emphatic, and it’s an answer that’ll be in an episode on the way.

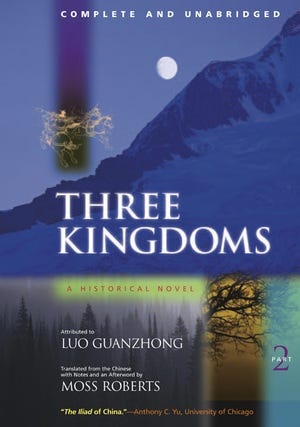

For those who read the newsletter, however, I’ll just reveal right now what he said: “Oh, easy: Three Kingdoms.”

Eternal Recurrence

This week, you’ll also hear Kaiser Kuo describe repetition within Journey to the West, which includes the repetition of the lawful tendency in Tripitaka clashing with the chaotic, rebellious tendencies of the Monkey King.

This recurring tension owes something to certain traditions—Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism—that shape Journey to the West. Those traditions are everywhere here, perhaps ironically, perhaps not. The Monkey King’s name is Sun Wukong—“Wukong” means “awakened to emptiness,” and it’s a Buddhist name, a profound name for a mischievous joker.

At one point, listening to a lecture on “a synthesis of Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism,” Sun Wukong starts “dancing, with enthusiasm.” The lecturer offers to teach a subcategory of Taoism, and Monkey asks what it would include.

“Summoning immortals, divining with yarrow stalks, and learning to pursue good and shun evil.”

“Will it make me live forever?” Monkey wanted to know.

“Not a chance,” Subodhi replied.

“Then I’ll have nothing to do with it,” Monkey responded.

(The above, and all Journey to the West quotes I use, come from Julia Lovell’s translation.)

There’s no absolute agreement on whether the book is an anarchic comedy or a controlled spiritual parable. It seems, somehow, to be both, in part because of spiritual traditions colliding in different ways—sometimes harmoniously, sometimes not. This week’s show thinks about the cosmopolitanism that brought such traditions together. Julia Lovell says:

The novel sprang from a much older set of legends about a real historical character who lived around 600–664 CE as a subject of the Tang empire in China. Now the Tang is one of the great eras of Chinese imperial expansion, when the empire extends from the edge of Persia in the northwest to the frontier with modern Korea in the northeast. Taizong, the emperor on the throne in Tripitaka’s time—he’s the character who in the novel dispatches Tripitaka off to India to fetch the sutras—Taizong is the vigorous, ruthless ruler who pushes the frontiers of his empire out so far.

And in the decades that follow this, the Tang empire is awash with cosmopolitan products and ideas. And still today in China, the Tang is celebrated as this period of phenomenal cosmopolitan flourishing of the empire and ideas throughout China.

More next week!

-Adam